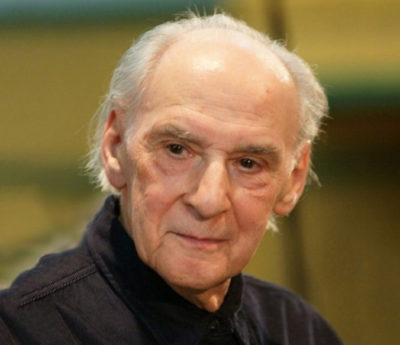

Joseph Horovitz 1926-2022

The Trust is deeply saddened to learn of the death on 9 February 2022 of composer and conductor Joseph Horovitz, Patron of the Trust since its foundation.

Joe was Milein’s oldest surviving friend (they first met in 1943) and he remained good friends with her and Hans for the whole of their lives.

Like Hans, Joe was born in Vienna, into a highly cultured middle-class Jewish family. And like Hans, he was forced to leave Austria in 1938, though rather more swiftly than Hans managed to do. It was only two days after the Anschluss that the eleven-year-old Joe was taken over the Italian border by his grandmother on a pretended skiing holiday to Merano, from whence they made their way to Belgium to be reunited with his parents, who by chance had been out of the country on a business trip at the time.

His father, Béla Horovitz, was co-founder of the Phaidon-Verlag, an influential literary press which had recently expanded to produce high quality art books at affordable prices. Béla had a close relationship with the British publisher Stanley Unwin, so was able to re-establish Phaidon in London as an imprint of George Allen & Unwin, under whose umbrella it became one of Britain’s leading art publishers. Joe remembered Stanley Unwin as ‘a phenomenal man’, who spoke excellent German, having cut his teeth in the German book trade in Leipzig in the early years of the century. ‘Therefore he understood what my father’s books were. He was the one who helped us in every possible way.’

The family settled initially in London, where Joe attended Regent’s Park School, established by Bruno and Alma Schindler in 1933 specifically to cater for the increasing number of child refugees coming to London. It was an ideal place, Joe remembered, ‘for me to start off, while my father was busy moving heaven and earth to get permission to stay in England’. He was lucky that his family had been able to emigrate together: some of his classmates never saw their parents again.

With the outbreak of war, the Horovitzes moved temporarily to Bath, where Béla’s friend the writer Stefan Zweig had a house, then returned to London briefly before being forced out again by the Blitz. They eventually settled in Oxford, which was where the 17-year-old Joe first met Milein Cosman, in the life classes of the Ruskin School of Drawing in 1943.

As a teenager, art was Joe’s consuming passion: ‘I still did not think music was going to be my profession: I was more interested in painting.’ Three afternoons a week he was given time off school to have lessons with Arthur Segal, the Romanian-born Berlin artist who was another of the many distinguished émigrés who found sanctuary in Oxford during the war. Segal was a pioneer of art therapy, and had established his ‘Painting School for Professionals and Non-Professionals’ in London in 1937, moving it to Oxford in 1940. Joe remembered his pupils as rather a ‘weird collection of people’, a mixture of ‘budding artists and people having painting therapy’. Apparently ‘Segal insisted on no drawing, but painting in monochrome,’ teaching Joe that ‘there is no such thing as a line, only a border between two patches of colour.’

By contrast, when he got to the Ruskin School ‘that was pure drawing – I never saw anybody paint at that time’. The Ruskin Master of Drawing was then Albert Rutherston, Fellow of New College, whom Béla Horovitz had consulted about the future education of his art-obsessed son. ‘Rutherston said, if your boy wants to draw and paint, get him to become a student at Oxford and then he can join the Ruskin School.’ Béla Horovitz took that advice, being keen that his son should get a degree; the only question was which subject Joe should apply to study. There was no undergraduate course in art at that time, and the only available degree in music was the postgraduate BMus. ‘So I studied Modern Languages – French and German – and got a pass degree in one year, so I was then a BA.’ This allowed Joe to progress to the BMus course, while continuing his art studies at the Ruskin School.

The Ruskin School was housed at the Ashmolean Museum, which was then extremely crowded, its own students having been joined by those of London’s Slade School of Art, evacuated to Oxford to escape the Blitz. ‘The Slade people included Milein, who was sitting next to me,’ Joe remembered. ‘We peeped across – I was an impressionable young man and she was a raving beauty aged 22, and everyone was falling over themselves about her. She was like a film star.’ Looking at her work, he was immediately struck by ‘the extraordinary strength of her drawings – they had enormous power in each line.’

As time went on, Joe’s musical studies took priority. ‘I began to realise that my drawings were less important to me than they had been and I became more serious about music. I realised that my paintings were artifacts not art, and they would not speak back to me. Music took over. I lost track of Milein after that, until my days back in London.’

Joe went to London at the recommendation of his Oxford tutor R.O. Morris, to continue his musical studies at the Royal College of Music, where he studied composition with Gordon Jacob. By then Milein was also in London, making a name for herself with her drawings of musicians, and living with Hans, whom Joe got to know though Viennese musical circles and through whom he renewed his acquaintance with Milein. His studies at the RCM were followed by a year in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger, which he financed by selling five of his paintings.

‘At that point I realised I was going to be some sort of musician,’ he recalled, though not necessarily a composer at this stage: ‘I was not driven to compose, I was driven to conduct and to arrange, and to make music.’

He took up his first post, as music director of the Old Vic in Bristol, in 1950, and this initiated a successful career conducting and composing for the theatre. He also conducted the Ballets Russes and the Festival Ballet, worked for Glyndebourne and was associate director of the Intimate Opera Company. During this period he wrote a series of successful works for the stage, including the acclaimed ballets Les Femmes d’Alger (1952) and Alice in Wonderland (1953) and the comic operas The Dumb Wife (1953) and Gentleman’s Island (1958).

In 1958, Joe got involved with the ebullient artist & musician Gerard Hoffnung’s ‘Interplanetary Music Festival’ – the second of his wildly popular concerts of musical jokes and parodies at the Royal Festival Hall. Joe’s contribution was Metamorphoses on a Bedtime Theme: allegro commerciàle in modo televisione – the ‘bedtime theme’ in question was the Bournvita television commercial (with its slogan ‘Sleep sweeter, Bournvita’). Commercial television in Britain had started only three years earlier, so its musical jingles were new to British ears and ripe for topical satire. Joe’s brilliant parodies in the style of Bach, Mozart, Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Verdi showed off his versatility and exquisite craftsmanship and were hailed by the press at the time as ‘the evening’s high moment’. Three years later he had an even bigger hit with his hilarious Horrortorio for the 1961 concert held in memory of Gerard Hoffnung after his untimely death.

In the 1960s Joe wrote the first of his works for brass ensemble, and he became a very significant composer of brass music, whose works have found an enduring place in the repertoire. It was the trumpeter Philip Jones, a friend from the RCM, who introduced him to brass instruments, and at the suggestion of Jones and the tuba player Roger Bobo, Joe wrote his first piece of brass chamber music, the Music Hall Suite for brass quintet of 1964, which was followed by many more works, including the Sinfonietta (1968), Ballet for Band (1983), Theme and Co-operation (1994) and the pioneering Euphonium Concerto (1972).

In the 1960s Joe wrote the first of his works for brass ensemble, and he became a very significant composer of brass music, whose works have found an enduring place in the repertoire. It was the trumpeter Philip Jones, a friend from the RCM, who introduced him to brass instruments, and at the suggestion of Jones and the tuba player Roger Bobo, Joe wrote his first piece of brass chamber music, the Music Hall Suite for brass quintet of 1964, which was followed by many more works, including the Sinfonietta (1968), Ballet for Band (1983), Theme and Co-operation (1994) and the pioneering Euphonium Concerto (1972).

Joe also wrote a trumpet concerto for Philip Jones, as well as concertos for violin, clarinet, bassoon, oboe and tuba, plus the glorious Jazz Concerto for harpsichord, strings and percussion, written for George Malcolm in 1965. That was inspired by walking in on Malcolm playing ‘the most amazing jazz improvisations’ during a break in rehearsals with the Philharmonia of London: ‘This is the most wonderful thing I’ve heard,’ Joe told him, ‘because I love jazz and I didn’t know you do that: really you should have a concerto written for you!’

In 1961, Joe was appointed Professor of Composition at the Royal College of Music, where he was much loved by his students for his patience and generosity, his openness to a wide variety of musical styles, and his high standards and deep concern for his craft. He continued to teach until his nineties, inspiring generations of students, many of whom went on to have significant musical careers of their own. His remarkable versatility and wide experience gave him a great ability to help his students see past the artificial divisions of fashion and style into what made real music.

His first teaching experience had been with the Army Education Corps during the war, while he was a student at Oxford. He taught music appreciation to the troops, an experience that he said had taught him a lot about how to communicate, and what worked and what didn’t: ‘That was the first time I had an audience.’

By the the 1970s he was also writing a considerable amount of film and television music, of which the most famous was perhaps Rumpole of the Bailey, with its unforgettable theme tune for four bassoons. Joe had a wonderful way of capturing the mood of a scene or a character in an instant, as was also evident in his works for the stage; the ballet dancer and choreographer Wayne Sleep said of his ballets, ‘You don’t need scenery: you can hear it in the music.’

Among his vocal and choral works of the 1970s were the oratorio Samson, the Lady Macbeth Scena for mezzo-soprano and piano, and the cantatas Summer Sunday and the award-winning Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo, an enduringly popular work written for children to a text by Michael Flanders, with whom Joe particularly enjoyed collaborating: ‘He was a wonderful instinctive musician: I did really like that man!’

Among his vocal and choral works of the 1970s were the oratorio Samson, the Lady Macbeth Scena for mezzo-soprano and piano, and the cantatas Summer Sunday and the award-winning Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo, an enduringly popular work written for children to a text by Michael Flanders, with whom Joe particularly enjoyed collaborating: ‘He was a wonderful instinctive musician: I did really like that man!’

Joe’s own favourite work of all his prolific output was his Fifth Quartet, which he wrote in 1969 for the 60th birthday of the art historian Ernst Gombrich, a family friend whose book The Story of Art had been one of Phaidon’s best known and biggest selling titles. It was premiered by the Amadeus String Quartet, and while he was writing it Joe was suddenly struck afresh by the extraordinary circumstances that had driven the composer, performers and dedicatee of this work from Vienna to London – ‘at which point I became conscious of a political content to this work.’ The ghost of a Viennese folk song and a distorted version of the Nazi Horst Wessel Lied made their way into the work to powerful effect. ‘This became a personal cry of mine. But it doesn’t end like that: it ends in a kind of resigned feeling of hope.’

Asked in an interview whether he had a message for younger generations, he stressed the importance of understanding who you are and where you come from. He described himself as lucky to be able to remember Vienna as it was, yet he was also clear that ‘I am a British composer.’ It was a complex identity: British but not English, Viennese-born but exiled, Jewish by religion but not writing Jewish music. All these cultural influences swirled around in his music, but above all was his supreme gift for musical communication. His was an original voice that was able to bring new ideas within an accessible tonal tradition, inventive, witty, with a glorious gift for melody and a mastery of harmony, counterpoint and imaginative orchestration.

The poet W.H. Auden once said, ‘The older one gets, the more one values the age of friendship, as if it were a vintage,’ and so it was with Joe and Milein. ‘Milein became a closer friend the older we got,’ said Joe. ‘Although her background was very German and mine was Viennese, we knew so many people in common that it became a very knowing friendship, because we understood each other’s backgrounds.’

In 2013, the German filmmaker Christoph Böll visited London to make a film about Milein. While he was there, Joe dropped round for tea and Christoph recorded this conversation between them – a full seventy years after they had first met, sitting and drawing next to each other in the Ashmolean Museum. It is being made available here for the first time:

Further links:

Obituaries are published in The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph, Classical Music Daily, The British Music Society, 4barsrest, and many other sources. The Royal College of Music’s tribute can be found here.

Among the interviews available online in which Joe talks about his life and music are the Refugee Voices Testimony Archive, in which Joe describes his escape from Vienna and his subsequent life in Britain, the Royal College of Music’s Singing a Song in a Foreign Land, in which Joe talks about his musical education, the Les Inventions documentary in which Joe talks about his Jazz Harpsichord Concerto, and Iwan Fox’s interview with Joe about his music for brass.

Available on BBC Sounds are the Radio 3 Composer of the Week programme in which Joe talks about his own music and that of his teacher, Gordon Jacob, and Debbie Wiseman’s Radio 4 documentary on Joe’s life and work, No Ordinary Joe.