Milein Cosman and the art of drawing

by Peter Black

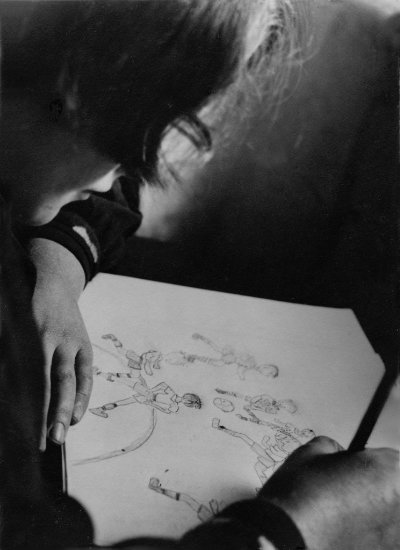

Milein Cosman was a German artist who dedicated her long life to making drawings, and almost all of them are images of people. She was born in Gotha in 1921, and her family moved to Düsseldorf in 1926. There, as a six-year-old girl, she drew compulsively, scribbling in a sketchbook underneath her desk when bored at school. “Drawing for me is a tick, it’s a kind of obsession. I remember … the thrill of dipping your pen in the ink and making a mark on the page.” However, life under the Nazis soon became impossible for Jews and in 1939 her family were forced to flee Germany, meaning that by far the greatest part of the artist’s life was spent in England. From 1939-42, Milein trained at the Slade School of Fine Art, an institution with a strong tradition of drawing. Her subsequent career as an artist was distinguished especially by the quality of her drawings. In wartime and post-war London, newspapers had not yet moved over irrevocably to the use of photography, and artist’s drawings still played an important role in recording human stories. For a time, Milein’s illustrations for books and journals reached a very wide audience. Whether it was for illustration or to create works for exhibition, drawing remained her principal activity almost until her ninetieth birthday.

Milein Cosman was a German artist who dedicated her long life to making drawings, and almost all of them are images of people. She was born in Gotha in 1921, and her family moved to Düsseldorf in 1926. There, as a six-year-old girl, she drew compulsively, scribbling in a sketchbook underneath her desk when bored at school. “Drawing for me is a tick, it’s a kind of obsession. I remember … the thrill of dipping your pen in the ink and making a mark on the page.” However, life under the Nazis soon became impossible for Jews and in 1939 her family were forced to flee Germany, meaning that by far the greatest part of the artist’s life was spent in England. From 1939-42, Milein trained at the Slade School of Fine Art, an institution with a strong tradition of drawing. Her subsequent career as an artist was distinguished especially by the quality of her drawings. In wartime and post-war London, newspapers had not yet moved over irrevocably to the use of photography, and artist’s drawings still played an important role in recording human stories. For a time, Milein’s illustrations for books and journals reached a very wide audience. Whether it was for illustration or to create works for exhibition, drawing remained her principal activity almost until her ninetieth birthday.

Milein had the good fortune to study in Oxford. The Slade was evacuated there from London during World War II and amalgamated with the Ruskin School of Drawing, which was then housed in the Ashmolean Museum. The Slade Professor, Randolph Schwabe (1885-1948), delegated the teaching of painting to Allan Gwynne-Jones so that he could concentrate on drawing. Schwabe was true to the School’s ethos, which maintained that they were continuing a tradition of scholarly draughtsmanship based on the old masters. To draw is to make an image by pulling (drawing) a medium across a surface, usually paper. The lines of a drawing are the traces of gestures, made by the artist with the moving point of the drawing implement. Therefore sketches and drawings made in front of the subject reveal in a very direct way the responses of the artist. Some drawings, however, just like paintings, are the product of preparation, thought and care in design, and while these processes are directed towards the creation of a finished result and lead towards beauty, they can also deprive a work of spontaneity and the authentic feeling of life being recorded which is to be found in all of Milein’s work. One of her closest friends at the Slade, Philip Rawson, went on to become an artist scholar who wrote two books about drawing which reveal an appreciation of spontaneous or lively drawing, which he clearly shared with Milein. Writing, in the age of photography, about the value of the hand-made image, Rawson talks of the artist establishing in a drawing ‘a well-developed language of marks [which] can convey far more about what it represents than any mere copy of appearances. Good drawing always goes beyond appearances.’ (Seeing Through Drawing, BBC, 1979).

At the end of her time at the Slade, Milein’s hand was already free and experienced. There are similarities between her Oxford drawings and some works by British painters, with echoes of Camden Town School artists. The painter and graphic artist William Nicholson had created in his Book of Blokes (1929) an anthology of rapidly sketched street figures, in a fine line of the kind Milein was now using, even if at that time she was not aware of Nicholson. She was continually sketching figures, often from behind, and she shared Nicholson’s love of street life. There is among her more conventional subjects, the people in bars, or sheltering in the underground, an elegance in the hand and attention to detail which disappears in later work, replaced by urgent and long-ranging, rapidly drawn marks with which to put down the scene in its entirety, authentically, on paper. Her paintings of this period, such as Oxford Scholar show a different, expressionist tendency and they are a reminder of the European visual inheritance which she brought with her to England and which links her with other exiled artists. Important creative friendships were established in the 1940s with, for example, Jacob Bornfriend, John Heartfield, Fred Uhlman and Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, all of whom settled in north London. Their work is still not as familiar as it should be, but these artists provided Milein with valuable moral support in establishing her own artistic identity in a foreign country.

Movement, which the artist has herself described as an obsession, has been noted as an important aspect in all previous writing about Milein, and it is a fundamental feature of the artist’s best work. It is not simply that she amazes us with her ability to capture the movement of musicians or dancers ‘in full flight’; what captivates is the authenticity of the experience revealed by the ‘language of marks’ on paper that trace a very sensitive and individual response. An artist’s best work is commonly made in the early years of their maturity, and it is also the case with Milein that many of her finest and boldest drawings date from the 1950s. Then, as a young woman in her thirties, living happily in London with the Austrian-born musician and writer Hans Keller, she took advantage of every opportunity to experience many remarkable performances in London by musicians and dancers. Her encounters with dancers from south-east Asia, beginning in 1946, were particularly important in developing this aspect of her work. She was introduced to Javanese dance by the celebrated John Coast who, after the fall of Singapore, had been imprisoned in Japanese labour camps and forced to work on the notorious Burma railway. There he came to appreciate the music and dance of the region and after the war he organised European tours for dancers such as the Sie brothers. Milein’s first drawings of these dancers appeared in Ballet in 1946 and later formed the basis for some of her most popular prints.

Dance drawings such as the striding Chinese Dancer from the troupe that visited London in 1955, form a large group of inspired works in which Milein demonstrated her mastery of a type of crayon used since the late eighteenth century and named after its original maker, Conté. The Conté stick is a versatile waxy drawing medium: it is square in section with a broad tip, with which tones can be created, while its sharp corners and edges permit the artist to draw precise and fine detail. Finally, the flat sides of the stick can be used ‘broadside’ to make gestural sweeps, swiftly marking out areas of tone, or even form. By the late 1940s, Conté was Milein’s preferred medium and it was the tool she chose when commissioned by the newspaper Heute to draw the cabinet ministers of the first post-war German government, established in Bonn under Konrad Adenauer in May 1949. The mastery of her touch is seen best in the head study of Hans Keller, in which the art critic David Cohen saw ‘strident contrasts of light and shade around a generous expanse of forehead’ and ‘a no-nonsense assertiveness, denoted by the dash of wayward hair’.

Milein’s energy and enthusiasm has meant that she possibly attended more concerts, ballets, and artistic performances of every kind than any living artist. Her dedicated observation of performers in action was one thing, but she has also consistently studied the great artists of the past to see how they dealt with problems of representation. Her own comments revealed an affinity above all with realists, especially those who drew and made prints, such as Goya or Daumier, or closer to the present, two specialists in the macabre, Ensor and Kubin. A group of ink drawings of the late 1950s provide an interesting example of how her work was informed by the experience of studying art in exhibitions. The reed pen is an expressive tool that was the favourite drawing method of Rembrandt in his later years, whether for landscapes or figures. In 1956, 350 years after his birth, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Museum Boymans van Beuningen in Rotterdam organised a major showing of his work in displays of, respectively, paintings and drawings. Milein’s favourite cousin Bob de Vries, who was director of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, was one of the Rembrandt show’s organisers. Her visit to see the drawings of this boldest and perhaps most difficult of all draughtsmen to emulate may explain the predominance of reed pen drawings in the year that followed, especially the group of Greek peasant figures drawn at Delphi in the summer of 1957.

The most significant development of Milein’s later career was her work as a printmaker. While she was a student in Oxford, the school acquired a lithographic press, and she was taught lithography by Harold Jones. Many years later, possibly as the demand for drawings as illustrations began to fall off because of changes in book production methods, Milein took up printmaking again. First she tried screenprinting and then, in the mid-1970s, took etching lessons with a Hampstead neighbour, Dolf Rieser (1898–1983). Two works from the early 1940s provide a striking premonition of her prolific production of prints of the period 1980-2000. The first is a lithograph portrait of the novelist Iris Murdoch, then a student at Somerville, and a friend from the moment that Milein approached her and asked if she could draw her. The other is Flight, an imaginative work that reveals both the trauma of exile as well as Milein’s familiarity with Germany’s great graphic tradition, with notable echoes of Käthe Kollwitz, especially the prints of the Weavers’ Revolt (Weberaufstand 1897). Printmaking requires several phased operations, and it is a process which seems likely to produce something static, but her prints retain both the immediacy of the glancing eye and the gifted graphic line of the artist’s hand.

Further reading:

Ines Schlenker, Milein Cosman: Capturing Time, Prestel (Munich, London and New York) 2019

Purchase the book: https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Milein-Cosman-by-Ines-Schlenker-author-Milein-Cosman/9783791357973