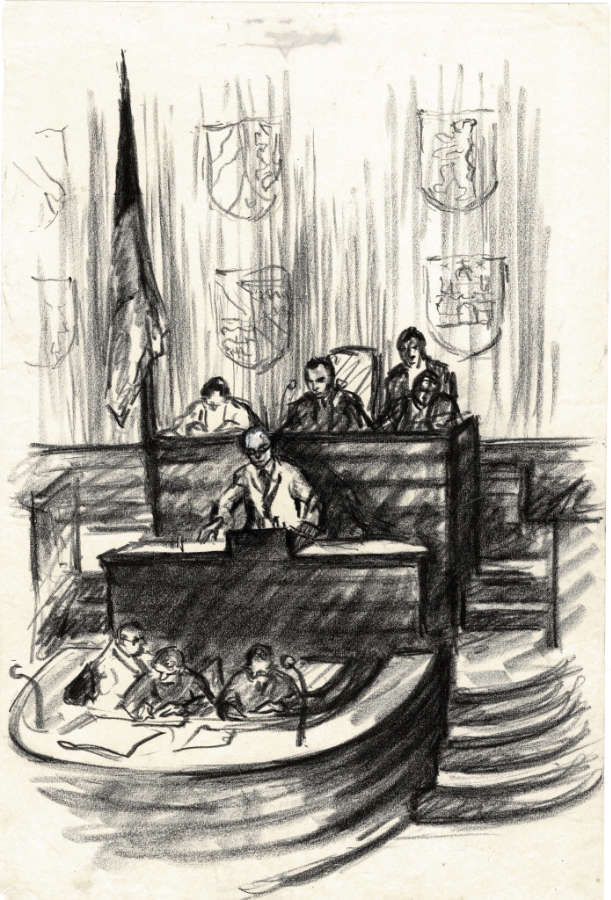

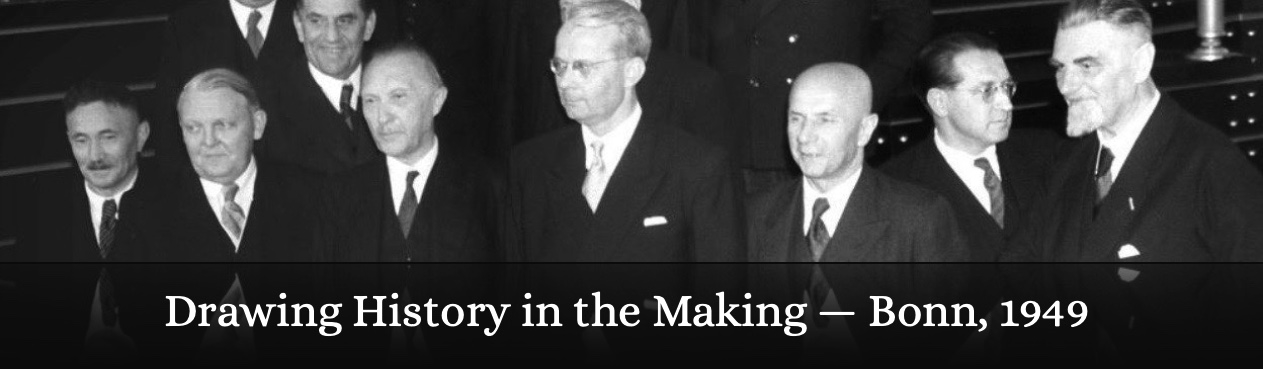

The pages above come from the 9 November 1949 issue of the magazine Heute. They capture an historic moment: when the first post-war elected government of the new Federal Republic of Germany took office in its freshly-converted parliament building on the banks of the Rhine in Bonn. A new state was rising from the ashes of the Nazi horror, bringing with it a hope of renewal on the one hand, but an inexorable solidifying of the iron curtain on the other.

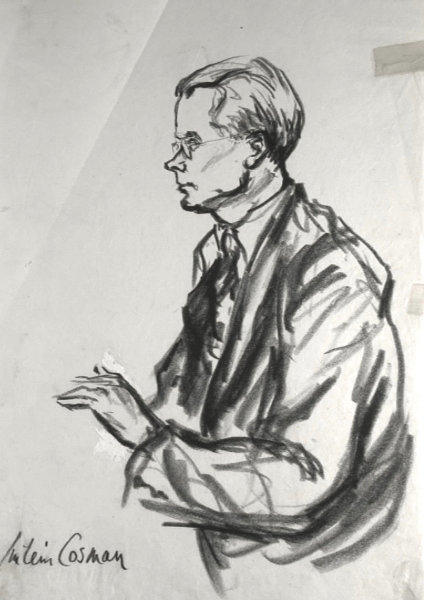

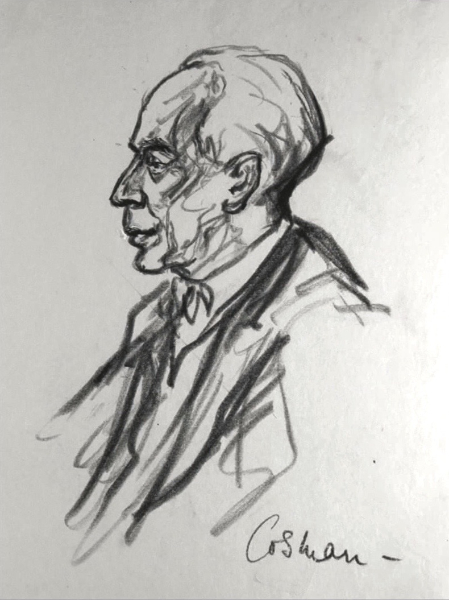

Entitled ‘Sketches from Bonn’, the layout of the article vividly suggested the immediacy of a first-hand eyewitness impression, published at speed — as befitted the importance of this moment in history. Milein Cosman’s drawings appear scattered as if they had just landed on the editor’s desk, with her collaborator Robert Müller’s words presented as though ripped from his notebook, complete with torn edges and a few hasty corrections. (The contrast with the more traditional presentation of their previous article for Heute (right) is clear.)

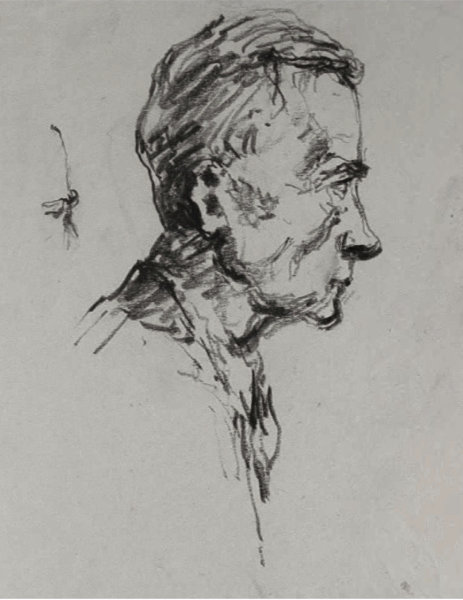

It was an assignment for which Milein was admirably suited, with her rapid drawing technique and ability to catch the essence of a person in the moment. Her commission for these drawings had come from Robert Müller, who ran the Heute office in London, a fellow German Jewish émigré originally from Hamburg. He and Milein had just collaborated on an illustrated feature for Heute about the third Edinburgh Festival, and he now travelled to Bonn alongside her, to write the text that was to accompany her drawings.

Heute magazine, like its sister publication Die Neue Zeitung, had been founded in October 1945 by the occupying American authorities. It was published in Munich, operating out of the same office building as had the defunct Nazi newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter. Modelled on the American illustrated magazine Life, then in its heyday, Heute enjoyed considerable success during the occupation period, with a circulation of over a million copies a fortnight.

Things were soon to change, with the shifting political situation, and despite Heute’s initial popularity it did not long survive the departure of the American occupiers, ceasing publication only two years after Chancellor Adenauer’s government took power. But in 1949 this was a prestigious commission for Milein and she jumped at the chance. Although she had just had success with her first solo exhibition at the Berkeley Galleries in May that year, and was in increasing demand as an illustrator, Milein was still struggling to earn a living.

Delighted with the news, she phoned her artist friend John Heartfield to tell him of her good fortune, only to be greeted by a distinctly negative response. A committed communist (he was to move to the German Democratic Republic in 1950), Heartfield despised the Western-leaning politics of Konrad Adenauer, and the division of Germany to which they would lead, and he tried to persuade her to turn the commission down. When she protested that she needed the money, he advised her to portray the cabinet members satirically, as he himself had done to such effect in his biting political photomontages before the war. Milein found this suggestion ridiculous: ‘I couldn’t suddenly change my skin and become a satirist. How dicey advice can be!’

In any case, she was not interested in her subjects as politicians — in fact she had never heard of any of them, which partly explains the extraordinary confidence with which she set about her task. ‘Looking back, I am amazed that I was not trembling in my shoes. But this detachment was, I should think, the clue to getting the job done. No hero worship was involved. No fear.’

She also managed to remain remarkably detached from the reaction of her subjects themselves, even when Chancellor Adenauer objected to her portrait of him. ‘So unflattering did Dr. Adenauer find my sketch of him that when Vicky [the political cartoonist Victor Weisz] went to draw him a fortnight later he was told that the Chancellor no longer wished to receive drawing visitors.’

Milein had sketched Adenauer not during a formal sitting, but in action at one of his press conferences — as always, she much preferred to draw her subjects engaged in their own activities and unconscious of the artist drawing them. She was rather pleased with the result, which she thought captured well his fox-like appearance, so was unreceptive to Adenauer’s suggestion that she come to his home to have another go — particularly when she realised that she was being invited not to draw the Chancellor himself, but simply to copy another artist’s portrait of which he approved.

She got on rather better with the SPD politician Carlo Schmid, a cosmopolitan and cultured figure who read Baudelaire to her and told her she should return to live in Germany, being just the sort of person the new state needed. ‘He impressed me tremendously at the time,’ she recalled, but perhaps because of that momentary lack of detachment, she found that her drawing of him turned out to be ‘the least pungent of the series.’

She worked at tremendous speed: ‘Within four days I managed to portray the Chancellor, Dr. Adenauer, and the Federal President, the entire Cabinet, members of the Opposition and the Allied High Commission,’ giving the editors at Heute a wealth of images from which to choose.

As well as portraits of individual politicians, Milein drew a variety of scenes of life in the Bundeshaus, as she followed the politicians around, listened to debates, visited offices and sat in on meetings.

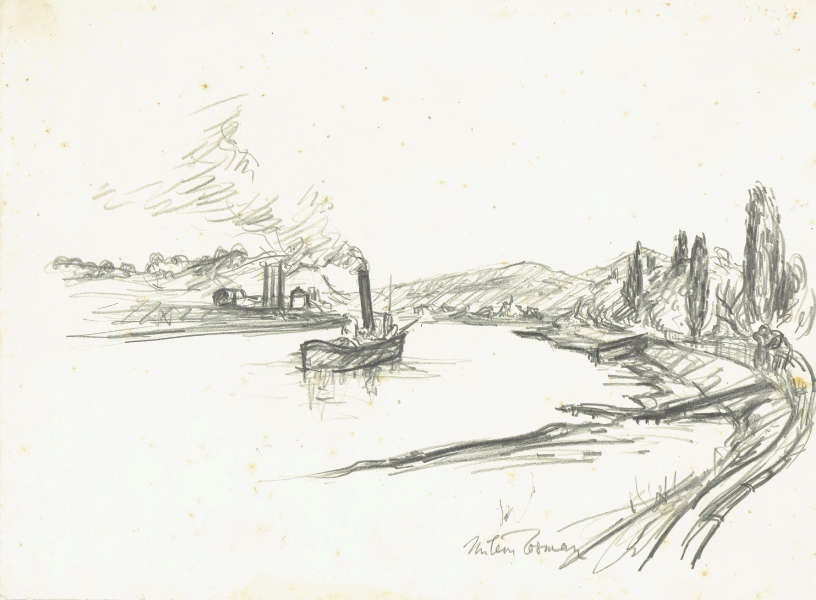

One of the best things about this commission for Milein was the fact that the provisional capital of the new West German state was now Bonn, so she could enjoy being back in the Rhineland, not far from the home in Düsseldorf where she had been brought up, hearing the Rhenish accent and drawing scenes of the river — a landscape that remained special to her for the rest of her life.

Her visit to Bonn in the autumn of 1949 was actually the second time that Milein had been back to Germany after the war. Her first visit had taken place just a few months earlier, in June 1949, when she had travelled across the country with a commission from the publisher George Weidenfeld to draw the bomb-damaged cities: hardly an easy task for her first return to her homeland.

While Milein was making these two visits back to Germany, her parents, who had been spent the war in Oxford, were making the difficult decision whether to return to live in Düsseldorf again. Her father’s steel factory had survived the war relatively unscathed, and he was able to reclaim ownership of it — a major factor in their decision, since they were struggling financially in England. Their former house in the Beethovenstrasse was in a sorry state, having been ransacked during the 1938 November pogrom and further damaged during the war, but some of their former friends were still living in the city — a fact which helped Hugo and Leni Cosmann decide to come back and start making a new life for themselves. Sadly it was not to last, as Hugo died only four years after their return. Leni stayed on until the 1970s, before she moved back to join Milein in London for the last few years of her life.

After their publication in Heute, Milein’s drawings of those historic scenes in Bonn in 1949, and the characters at the centre of them, lay in a drawer in her home in London for decades. They were acquired by the German Government Art Collection shortly before her death and exhibited for the first time as a complete collection, in an exhibition devoted to Milein’s work at the Bundestag in Berlin during April and May 2022.

This exhibition, ‘Milein Cosman: Porträts aus Politik und Kunst’, was opened by Bundestag President Bärbel Bas on 6 April 2022 and and a documentary film about it can be viewed below. The exhibition brochure can be downloaded here (in English) and here (in German).