Milein Cosman founded the Trust in 2006. But its story really begins twenty years before that, after the death of her husband, Hans Keller. Hans died in November 1985, at the relatively early age of 66. He had suffered from motor neurone disease, but had not let it stop his writing and teaching, or damp his indomitable spirit. When Milein’s own eyesight began to fail in her later years, she did not let that stop her either, carrying on drawing as long as she possibly could.

Both Milein and Hans had been prodigiously prolific throughout their lives, so their home in Frognal Gardens in Hampstead was filled with her artwork and his writings. After Hans died, Milein’s thoughts naturally turned to the maintenance of his legacy — and later, as the years passed, she also began to consider the preservation of her own enormous portfolio of work.

In this, Milein was never alone. As well as being filled with art and music, Frognal Gardens was always full of friends. Such was the regard in which she and Hans were held, both as artists and as people, that many friends and admirers were eager to help Milein preserve their work for the future.

Hans’s massive archive of papers posed the first challenge, and Milein turned for help to their friend Julian Hogg. Julian had worked with Hans at the BBC, and after Hans’s retirement had been his amanuensis for the last five years of Hans’s life, enabling him to keep writing right up to his death. Letters, essays, reviews, and the whole of Hans’s final book (The Great Haydn Quartets) had all been dictated to Julian.

The list of Hans’s publications was already very long, but there was still more unpublished. One day Milein opened a drawer to find the manuscript of a whole unpublished book — this turned out to be Criticism, which Hans had written in 1976, but never got round to publishing, although Faber & Faber had been asking him about it for years. Milein and Julian took the manuscript to Faber, Julian transcribed and edited it, and the book was published in 1987.

The list of Hans’s publications was already very long, but there was still more unpublished. One day Milein opened a drawer to find the manuscript of a whole unpublished book — this turned out to be Criticism, which Hans had written in 1976, but never got round to publishing, although Faber & Faber had been asking him about it for years. Milein and Julian took the manuscript to Faber, Julian transcribed and edited it, and the book was published in 1987.

Criticism was not the only unpublished manuscript to see the light of day after Hans’s death. Christopher Wintle, then of Goldsmiths, University of London (where Hans had given classes in analysis) and later of King’s College London, was to become responsible for many more. He and the critic and composer Bayan Northcott had already discussed with Hans himself a selection of seminal essays for Cambridge University Press (this was to become Essays on Music, published in 1994 and reissued in 2005), and in the months after Hans’s death Christopher edited a memorial symposium for him, published in Music Analysis, the journal for which Hans had written the inaugural essay in 1982.

Criticism was not the only unpublished manuscript to see the light of day after Hans’s death. Christopher Wintle, then of Goldsmiths, University of London (where Hans had given classes in analysis) and later of King’s College London, was to become responsible for many more. He and the critic and composer Bayan Northcott had already discussed with Hans himself a selection of seminal essays for Cambridge University Press (this was to become Essays on Music, published in 1994 and reissued in 2005), and in the months after Hans’s death Christopher edited a memorial symposium for him, published in Music Analysis, the journal for which Hans had written the inaugural essay in 1982.

Christopher took over from Julian the role of Hans’s literary executor, generating continued scholarly interest in Hans’s work and a constant flow of publications. A significant part of this was the series of books published by Plumbago Books, the new specialist press which Christopher founded in 2000. The very first Plumbago book to appear was Hans’s Jerusalem Diary, wonderfully illustrated by Milein’s drawings, which won the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Book of the Year prize in 2001.

Christopher also negotiated on Milein’s behalf the establishment of the Hans Keller Archive at the University Library in Cambridge, where composer Alexander Goehr (who had worked with Hans at the BBC in the 1960s) was Professor of Music, and Hugh Wood, another of Hans’s composer friends, was Fellow of Churchill College. The Faculty of Music unanimously agreed to fund an archivist, and work began in January 1996. One of Christopher’s postgraduate students, Alison Garnham, became the first Hans Keller archivist and later the author of more Keller publications. Such was the size of the archive, however, that it was to be a quarter of a century before the full catalogue would finally be completed by the current archivist, Susi Woodhouse.

Another Cambridge connection was the art dealer and curator Peter Black, later Curator at the Hunterian Gallery at Glasgow University, but then living and working in Cambridge. He had first met Milein and Hans in 1984, when he was a young man just out of university, working in his first job in the London art world and lodging in the house of Milein’s great friend, the Viennese-born painter Marie-Louise von Motesiczky. Milein had taken the young Peter under her wing, introducing him to more of her artist friends and taking him to etching classes with her, and they quickly became firm friends.

Peter helped organise a major retrospective of Milein’s work in 1988 at the Stadtmuseum in Düsseldorf, the city in which Milein had spent much of her childhood (her parents had moved there when she was five) and which she had regularly visited after her parents returned there in the post-war years.

In 1990, Peter organised another exhibition at Clare Hall in Cambridge (where his father was Fellow in English). This was followed by another solo exhibition at the Belgrave Gallery in London in 1996.

31 March 2001 was Milein’s 80th birthday. Three weeks later she flew to Vienna for the international Hans Keller Symposium hosted by the Arnold Schoenberg Center and the University of Music and the Performing Arts in Vienna. This event also marked the publication by Peter Lang of the complete edition of Hans’s Functional Analysis scores, edited by Gerold Gruber (of the University of Music and the Performing Arts), with the assistance of Hans’s friend (and joint dedicatee of Functional Analysis No.9), the pianist Susan Bradshaw.

Back row L-R: Levon Chilingirian, Christopher Wintle, Ulrike Anton, Julian Hogg, Alison Garnham, Leo Black, Hugh Wood, Gerold Gruber.

Front row L-R: Mark Doran, ?, Christopher Hailey, Donald Mitchell, Milein Cosman, Charles Sewart.

In 1998, Peter Black moved to Glasgow, to take up the post of Curator of Prints at the Hunterian Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow. Milein’s older brother, Cornelius Cosman, had studied at Glasgow University in the 1930s, graduating with a BSc in Applied Chemistry in 1938 (it had been he who had persuaded Milein in 1939 to come and study in Britain too – a decision that may have saved her life). In 2002, Milein decided to give a collection of her prints to the Hunterian in memory of her brother, and the Gallery then supplemented this generous gift by purchasing a selection of drawings the same year. Later, in 2014, the Trust gave to the the Hunterian a further group of drawings which had been exhibited at Gotha, Milein’s and Cornelius’s birthplace.

After Peter went to Glasgow, Julian remained busy at Frognal Gardens, helping Milein begin the sorting of her vast archive of drawings and prints. As they worked, he was continually struck by the wealth of hidden gems they were unearthing in the process. One day, as he waited for a friend to arrive for a concert, Julian had the idea of mounting an exhibition of Milein’s drawings of musicians in a concert hall rather than a gallery setting. As it happened, the friend he was awaiting that day was his former BBC colleague Robin Lough, who was then a trustee of the Wigmore Hall, where the idea was enthusiastically received — and on 29 March 2005, two days before Milein’s 84th birthday, the exhibition opened.

(photograph: John Batten).

Milein’s drawings and prints were exhibited alongside a selection of photographs by Clive Barda, also well known for his portraits of musicians. The exhibition was originally scheduled to last a few weeks, but such was the reaction from concert-goers to Milein’s drawings that the Wigmore Hall quickly asked to buy the whole collection for permanent exhibition, and they remain on public view there to this day.

Another significant development around this time, facilitated by Christopher Wintle in 2004, was the acquisition by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford of an important collection of Milein’s drawings and sketchbooks dating from her student days at the Slade School of Art during the war, when the Slade was evacuated to Oxford.

A fourth substantial institutional acquisition of Milein’s art took place in 2007, when her second cousin, Leo Goldschmidt donated a collection of 50 of her drawings and 32 prints to the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels.

Hunterian Gallery, Glasgow

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Wigmore Hall, London

Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels

Horovitz

Milein had been thinking for some time about the establishment of a Trust, for the preservation of her and Hans’s work and the promotion of music and art. She was also keen to set up support for individual musicians and artists, reflecting the help she herself had received as a young artist from the Quakers. Initially she considered leaving it to the executors of her will to sort out after her death, but in the end decided it would be better to set it up herself and direct its early work — in particular so that she could inform the cataloguing and archiving of her artwork.

November 2006 was the date of the formal establishment of The Cosman Keller Art & Music Trust. Milein appointed four founding trustees: Julian Hogg, Christopher Wintle, Peter Black and Andrew Cherniavsky. Andrew was a close neighbour of hers in Hampstead and an experienced investment banker, so admirably suited to act as the Trust’s Treasurer. Peter became her artistic executor, alongside Christopher’s literary executor work for Hans. She asked Julian to be the Chair.

Several of Milein’s friends became Patrons of the Trust: the artist Ana Maria Pacheco, the composers Hugh Wood and Joseph Horovitz, the poet Dannie Abse, and the violinist Levon Chilingirian.

Milein herself was President of the Trust and attended some of its early meetings. However she was also kept busy with demands for her work. In 2008 she had three more solo exhibitions: one in Pulsnitz, Dresden, and two in London, at the Austrian Cultural Forum and at Burgh House, Hampstead — where Milein was also interviewed for the AJR Refugee Voices archive.

With Hans’s archive settled in Cambridge, the cataloguing of Milein’s own archive was a priority for the Trust. At the recommendation of Milein’s friend, the photographer Dorothy Bohm, and her daughter Monica, Jane Cassini joined Milein’s Frognal Gardens ‘family’ in September 2008 as the Cosman archivist. At the start of the process, Jane worked closely alongside Milein herself, absorbing her thoughts on each drawing or print and hearing her vivid account of the people and scenes depicted. Jane also played an increasingly important role in the curating of Milein’s exhibitions, as well as providing invaluable support for research into Milein’s work.

Another important aim of the Trust was the support of young musicians and artists, and it began awarding bursaries at this time. The first two musicians to receive its support were the soprano Sofia Larsson and the violinist Margaret Dziekonski. This activity was later to be expanded and formalised with the establishment of the Hans Keller Scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music.

The Trust supported a series of publications over the next few years, including two books on individual composers that combined Hans’s writings and Milein’s drawings: Stravinsky: the Music Maker, edited by Martin Anderson in 2010, and Britten: Essays, Letters and Opera Guides, edited by Christopher Wintle and Alison Garnham for Britten’s centenary in 2013 (featuring an ‘operatic sketchbook’ of drawings done by Milein at the rehearsals and performances of a series of Britten’s operas).

The Trust supported a series of publications over the next few years, including two books on individual composers that combined Hans’s writings and Milein’s drawings: Stravinsky: the Music Maker, edited by Martin Anderson in 2010, and Britten: Essays, Letters and Opera Guides, edited by Christopher Wintle and Alison Garnham for Britten’s centenary in 2013 (featuring an ‘operatic sketchbook’ of drawings done by Milein at the rehearsals and performances of a series of Britten’s operas).

A particularly significant publication for Milein herself came in 2012: this was Lebenslinien/Lifelines. Although Milein’s work had illustrated countless books by now, this was the first book devoted solely to her art since her Musical Sketchbook of 1957. The idea of a new book had first been suggested by Sabine Schubert, organiser of the recent Dresden exhibition; the book was edited by Julian Hogg and Thomas Schumann, with the help of Jane Cassini and Caterina Thiel, and published by EditionMemoria, with financial support from the Trust.

A particularly significant publication for Milein herself came in 2012: this was Lebenslinien/Lifelines. Although Milein’s work had illustrated countless books by now, this was the first book devoted solely to her art since her Musical Sketchbook of 1957. The idea of a new book had first been suggested by Sabine Schubert, organiser of the recent Dresden exhibition; the book was edited by Julian Hogg and Thomas Schumann, with the help of Jane Cassini and Caterina Thiel, and published by EditionMemoria, with financial support from the Trust.

Fortuitously, a review of Lebenslinien was seen by the Mayor of Gotha, the city in Thuringia where Milein was born. At that time, Gotha was building its new Kunstforum, and Milein was invited to be the subject of its inaugural exhibition in 2014. This was followed by another exhibition in 2015 in Düsseldorf, where Milein had spent much of her childhood. Milein was the guest of honour at the opening of the Gotha Kunstforum — it was the first time she had been back to her birthplace for 80 years. The filmmaker Christoph Böll made a documentary film about Milein for the exhibition in Gotha, showing her at home and out with friends in Hampstead, and interviewing her at length about her early life.

More detailed research on Milein’s life and work was meanwhile being undertaken by the art historian Ines Schlenker, whom the Trust had commissioned in 2011 to write an illustrated biography. This was to become Capturing Time, published by Prestel in 2019.

The Trust’s personnel underwent some changes around this time. Andrew Cherniavsky retired as Treasurer in 2013 and was succeeded by David Brilliant, a former director of Credit Suisse.

The following year the Trustees decided to expand their number and Alison Garnham and Andrea Rauter joined the Board, followed by David Scrase in 2016. David Scrase, formerly Assistant Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, was also a trustee of the Motesiczky Trust and a near neighbour of Milein’s in Hampstead. Andrea Rauter was an experienced teacher and concert manager who had become good friends with Milein at the time of her 2008 exhibition at the Austrian Cultural Forum, where Andrea was Music and Special Projects Manager. This was not their first meeting, however, since Hans and Milein had known Andrea’s parents and visited their home when Andrea was a child — indeed Hans had been interned on the Isle of Man during the war with Andrea’s father, the pianist Ferdinand Rauter.

(photograph: Norbert Meyn)

Alison Garnham had been succeeded at the Hans Keller Archive in Cambridge by Susi Woodhouse, a senior music librarian and archivist of wide experience. With Hans’s centenary due in 2019, Susi and Alison were determined not only to complete the catalogue of his archive, but also to collaborate on a new biography to mark the occasion. This was to become Hans Keller 1919-1985: A musician in dialogue with his times, published by Routledge in 2019. In the same year, Christopher Wintle’s Plumbago Books brought out its sixth Keller publication for the centenary: Hans’s famous lectures on Beethoven’s Op.130 quartet.

Institutional interest in Milein’s work was now growing apace and Andrea Rauter facilitated two particularly important acquisitions in 2017. The Royal College of Music Museum acquired 1,300 portraits of musicians, which a grant from the Pilgrim Trust enabled to be fully documented and digitised. A permanent display of Milein’s work is now on view in the Museum’s new building. Also in 2017, a large collection of Milein’s images of dancers was acquired by the University of Salzburg, as part of its Music and Migration Collection. This comprises 260 drawings, 100 etchings and 8 oil paintings, together with sketchbooks and other materials related to dance.

These two acquisitions were among the last events in the Trust’s life that Milein herself knew about. She was now 96 and growing increasingly frail. Thanks to Julian, her many other friends, and a team of wonderful carers, especially Mary Odgers, Milein was able to stay at home in Frognal Gardens until her death, which came peacefully on 21 November 2017. Among the many moving tributes from family and friends at her funeral, Levon Chilingirian and Simon Rowland-Jones (who had both known Milein since they were coached by Hans in the early 1970s) played the Andante cantabile from Mozart’s K.424.

These two acquisitions were among the last events in the Trust’s life that Milein herself knew about. She was now 96 and growing increasingly frail. Thanks to Julian, her many other friends, and a team of wonderful carers, especially Mary Odgers, Milein was able to stay at home in Frognal Gardens until her death, which came peacefully on 21 November 2017. Among the many moving tributes from family and friends at her funeral, Levon Chilingirian and Simon Rowland-Jones (who had both known Milein since they were coached by Hans in the early 1970s) played the Andante cantabile from Mozart’s K.424.

The following summer Milein’s many friends gathered again to remember her, at Hampstead’s Burgh House, where Ben Johnson and Roger Vignoles gave a performance of some of her favourite Schubert and Britten songs. Among the most touching of the many lovely stories of Milein that were shared on that day was composer Joseph Horovitz’s memory of his first meeting with her in the life-drawing class at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford during the war — apparently one look at her easel convinced him that his own vocation was music, rather than art!

Frognal Gardens, where Hans and Milein had lived since 1967, was now to be sold, and the Trust therefore transferred Milein’s remaining archive to new accommodation, where cataloguing and digitisation continued. Andrea Rauter and her partner Gerald Davidson undertook the huge task of sorting Milein’s personal correspondence and library of books, and her art books found a new home in the Hampstead School of Art, together with her easel, made and given to her by Robert Indiana. The house clearance also revealed a surprise for Susi Woodhouse, when Gerald found a large (and very dusty) cache of Hans’s early papers in the loft. This ‘Attic Anhang’ put an end to her hopes of finishing the cataloguing in time for Hans’s 100th birthday, but there was some compensation in the fascinating documents unearthed.

Gerald Davidson packing up books for the HSoA

Gerald and Alison discovering a letter to Hans from Schoenberg

Milein had lived in Hampstead for a total of 70 years, first in lodgings on Christchurch Hill and then in a small studio on Willow Road, after which she and Hans bought their first house at 50 Willow Road, where they lived for twelve years until they moved to Frognal Gardens. The house at Frognal Gardens is set back from the road, almost invisible behind the tunnel of wisteria that Milein planted along the garden path. The house at 50 Willow Road, on the other hand, stands right on the street, and it was there that a blue plaque commemorating Hans and Milein was erected by the Association of Jewish Refugees in 2019, Hans’s centenary year. The house is now owned by Milein’s friends Philippe Sands and Natalia Schiffrin, who held a party to mark the unveiling of the plaque. Among the speakers at this event was Ena Blyth, Hans’s niece, who had many years of memories of the house, not only from Hans and Milein’s time, but also from the subsequent years when her mother, Hans’s half-sister, had also lived there.

2019 was the year of Hans Keller’s centenary – so it was a hectic year for the Cosman Keller Trust, with many concerts, talks and other events marking Hans’s 100th birthday, as well as exhibitions of Milein’s art.

The Trust had been supporting young musicians at the Royal Academy of Music since 2011, and a new award in the name of Hans Keller was created in 2013. The sale of Frognal Gardens allowed the Trust to increase considerably the scale of its support, and the Hans Keller Scholarship for string players is now one of the Academy’s top awards. The student who won the award in Hans Keller’s centenary year was the gifted cellist Yanyan Lin (pictured here performing in the Duke’s Hall).

Having established this scholarship and seen the Trust through the Hans Keller centenary year, Christopher Wintle decided to retire from the board of trustees in 2020, after 35 years’ service to Hans’s legacy.

David Brilliant had also retired from the board in 2019 and Andrew Mosely (director and CFO of the management consultancy Metapraxis) became the Trust’s new Treasurer.

The beginning of 2020 saw another major institutional acquisition of Milein Cosman’s art, when a collection of 93 drawings was donated to the Imperial War Museum in London. The drawings were made during the 1940s and provide an invaluable portrait of British social life during that period. The Imperial War Museum’s oral history collection includes a 1997 interview with Milein by the historian Daniel Snowman, which can be heard here.

Like the rest of the world, the Trust found its plans for 2020 radically altered by the Covid-19 crisis. Public events had to be cancelled, and the Trust instead made a series of emergency grants to support musicians and artists. These included contributions to the Help Musicians Coronavirus Financial Hardship Fund, to the fund established by the Royal Academy of Music for students in hardship due to the lockdown, to the bursary funds of both the Hampstead School of Art and the Yehudi Menuhin School, and to the emergency fund of the Young Classical Artists Trust, to help outstanding young musicians suffering the cancellation of all their concerts at the outset of their professional careers.

David Brilliant

Andrew Mosely

At the end of October 2020 came the tragic death of David Scrase, Cosman Keller Trustee since 2016. When he joined the Trust, David had recently retired from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, where he had spent many years as Keeper of Paintings, Drawings and Prints and then Assistant Director of Collections, amassing an unsurpassed knowledge of the collections and directing a remarkable period of acquisitions for the museum. He had a deep understanding of drawing and a profound knowledge of the history and making of art; he was also a generous, charming and witty friend and colleague, who will be very sorely missed by all who had the good fortune to know him. A tribute to his life and work at the Fitzwilliam can be found here. Obituaries were also published in The Times and The Daily Telegraph.

2020 was a dreadfully difficult year. Nevertheless, the Trust looked forward with hope to 2021, for 31 March 2021 would have been Milein’s 100th birthday. When the pandemic struck, several exhibitions and events were already planned to mark her centenary year, and work continued throughout the lockdown to bring as much as possible to fruition.

![]()

The Trust published a special 2021 Calendar to mark Milein’s centenary, featuring a selection by Julian Hogg and Jane Cassini of portraits of some of the musicians she encountered in the 1940s and 1950s – including Igor Stravinsky, who was (apart from her husband, Hans Keller) her most frequent subject. Milein first met him at the premiere of The Rake’s Progress in Venice in 1951, and afterwards took every opportunity she could to draw him in rehearsal and concert: he was, she said, ‘one of the strongest visual impressions of my life’. The fiftieth anniversary of Stravinsky’s death was on 6 April 2021, just one week after Milein’s centenary.

Unfortunately, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic meant that the exhibitions and events planned for Milein’s centenary in the spring of 2021 (see here for details) had to be postponed. Celebrations of Milein’s 100th birthday on 31 March 2021 therefore moved temporarily online, and the Trust created a virtual Centenary Exhibition, curated by Milein’s artistic executor, Peter Black. This opened in March 2021 and can be viewed here.

Meanwhile, at the beginning of 2021, Peter and his fellow trustees were delighted to welcome a new trustee to their number: Jennifer Ramkalawon, Curator of Western Modern and Contemporary Graphic Works in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum.

An important development in Milein’s centenary year was the establishment of the Milein Cosman Scholarship for Drawing at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, funded by the Trust. This scholarship, to be awarded to an outstanding postgraduate student, marks not only Milein’s centenary but also the 150th anniversary of the foundation of the Slade, where Milein herself studied during the Second World War. Milein had arrived in London as a refugee from Nazi Germany shortly before war broke out, and by the time she started her studies in the autumn term of 1939 the Slade had been evacuated to Oxford. Her time there was a formative period in her development, particularly memorable because of the creative stimulation of her many friendships with writers and musicians as well as artists. One friend who still retained vivid memories of Milein in Oxford was Trust Patron Joseph Horovitz, who first met her in the drawing classes of the Ruskin School of Art (with which the Slade was amalgamated for the duration of the war) in 1943. His recollections of their meeting, together with more information about Milein’s time at the Slade in Oxford, can be found here. The inaugural winner of the Milein Cosman Scholarship was the remarkable artist Hannah Uzor, who joined the Slade’s MA programme in September 2021: more information about Hannah and her art can be found here.

An important development in Milein’s centenary year was the establishment of the Milein Cosman Scholarship for Drawing at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, funded by the Trust. This scholarship, to be awarded to an outstanding postgraduate student, marks not only Milein’s centenary but also the 150th anniversary of the foundation of the Slade, where Milein herself studied during the Second World War. Milein had arrived in London as a refugee from Nazi Germany shortly before war broke out, and by the time she started her studies in the autumn term of 1939 the Slade had been evacuated to Oxford. Her time there was a formative period in her development, particularly memorable because of the creative stimulation of her many friendships with writers and musicians as well as artists. One friend who still retained vivid memories of Milein in Oxford was Trust Patron Joseph Horovitz, who first met her in the drawing classes of the Ruskin School of Art (with which the Slade was amalgamated for the duration of the war) in 1943. His recollections of their meeting, together with more information about Milein’s time at the Slade in Oxford, can be found here. The inaugural winner of the Milein Cosman Scholarship was the remarkable artist Hannah Uzor, who joined the Slade’s MA programme in September 2021: more information about Hannah and her art can be found here.

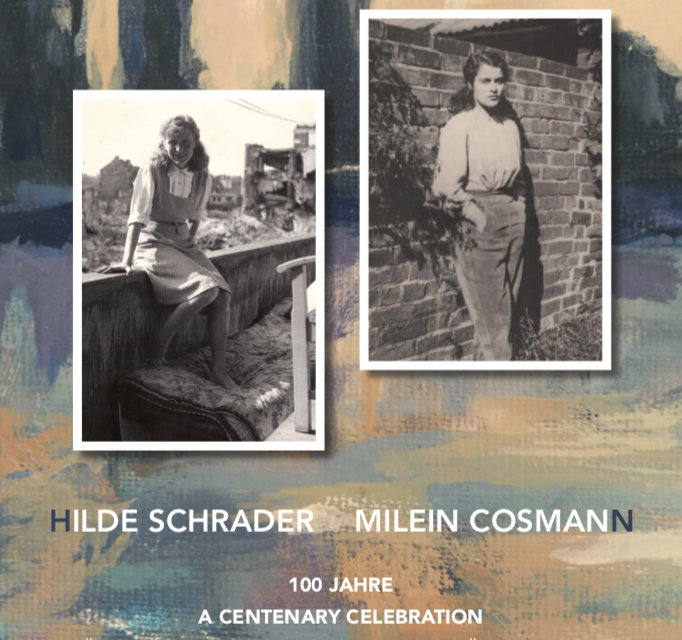

Although many of the events planned to celebrate Milein’s centenary were postponed by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic (including a very significant exhibition at the Bundestag in Berlin, which opened a year later: see here for details), two lovely exhibitions were able to open before her centenary year was out, thanks in particular to the efforts of Julian Hogg and Caterina Thiel. In October, an exhibition devoted to Milein and her childhood friend and fellow-artist Ilde Schrader opened at the Stadtmuseum in Düsseldorf, where Milein and Ilde had grown up together. This was followed in December by a centenary exhibition in Hampstead (at the Hampstead School of Art), where Milein lived almost all her adult life.

Also in December, the Trust held a special celebration of Milein’s centenary at the Royal College of Music, whose Museum now houses the largest collection of her art anywhere in the world. The Museum’s original acquisition of 1,300 drawings of individual musicians in 2017 has now been supplemented by further collections of drawings of opera and ensembles, and a number of portraits of Hans Keller. A permanent exhibition of Milein’s art is now on display in the Lavery Gallery.

After a reception at which the final artworks were formally received by the Museum’s Curator, Professor Gabriele Rossi Rognoni, a concert in memory of Milein and Hans was held in the College’s Amaryllis Fleming Hall, in which Sini Simonen, David Waterman and Jean-Sélim Abdelmoula gave a thrilling performance of piano trios by Haydn and Brahms, and the César Franck violin sonata.

2021 also saw the launch of a major new initiative for the Trust: the Hans Keller String Quartet Project. For Hans Keller, the string quartet was the most purely musical form of composition and the closest to his heart — and his contribution to its development in the second half of the twentieth century was immense. He coached many of the leading British ensembles of the time — including the Chilingirian, Endellion, Dartington and Lindsay Quartets — and during his 20 years at the BBC he not only developed performance opportunities and enabled the best quartet-playing to be heard, but also did much to broaden awareness of this remarkable repertoire. Through his own broadcast talks and lectures around the country he made an outstanding contribution to the education of the audience for chamber music, and he had a unique ability to speak meaningfully both to musicians and their public at the same time. He inspired many composers to write new works for string quartet, including Benjamin Britten, who dedicated his own Third String Quartet to the man who, he said, ‘knows more about the string quartet, and understands it better, than anybody alive’.

As part of this project the Trust is delighted to be supporting the Castalian String Quartet in a new residency at Oxford University, the Adelphi Quartet in partnership with the Young Classical Artists Trust, and the Consone Quartet together with the Mithras Trio as Chamber Fellows of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where Keller himself had coached young quartets in the 1980s. As well as supporting performers, the Trust has begun to commission new works for string quartet — the first of these, Saffron Dusk by Bushra El-Turk, was premiered by the Adelphi Quartet at the Wigmore Hall, and a new work from Mark-Anthony Turnage for the Castalian String Quartet will be announced in 2022. Also in 2022 the Trust will begin a new partnership with Richard Ireland’s ChamberStudio to create the Hans Keller Forum, which will provide residential courses in the college/university vacations offering specialised coaching and support to student chamber ensembles.

One of the sadnesses of 2121 was the death on 14 August of composer Hugh Wood, a good friend of Hans and Milein, and a Patron of the Trust since its foundation.

One of the sadnesses of 2121 was the death on 14 August of composer Hugh Wood, a good friend of Hans and Milein, and a Patron of the Trust since its foundation.

They met in 1958, when Hans came for the first time to teach at the Dartington Summer School of Music, which Hugh had been attending as a student since its inception ten years before. ‘My oldest memory is of Hans sitting on the lawn at Dartington, surrounded by young musicians,’ wrote Hugh, for whom the experience was of profound importance. ‘He taught a whole generation of us. Only a lucky few of us formally, the rest by this process of friendly, undogmatic osmosis of a remarkable personality into one’s own.’

Hans was an admirer of Hugh’s music, and Hugh was always grateful for Hans’s ‘constant solicitude for one’s own work, about which he showed himself the most caring of critics, the most benevolent of masters and the truest friend.’ After Hans’s death Hugh was a staunch supporter of Milein’s efforts to preserve his legacy, and when she founded the Trust he became a Patron.

The Trust’s tribute to Hugh can be read here.

Another young musician who encountered Hans at Dartington a few years afterwards was Julian Hogg, who met him when setting up the stage for one of Hans’s lectures in 1964. Intrigued by Hans’s simple requirements (a glass of water and an ashtray) he was deeply impressed once he heard Hans lecture, pacing to and fro across the stage, chain-smoking and discussing the music in profound detail without a single note or glance at a score.

Later, Julian joined the BBC, where Hans was then in charge of orchestral and choral music, and they became good friends. Then in the 1980s, after Hans had retired and was beginning to suffer the effects of motor neurone disease, Julian became his amanuensis, going regularly to Frognal Gardens to take dictation, and typing thousands of pages of letters, reviews, articles, and the whole of Hans’s final book, The Great Haydn Quartets.

After Hans’s death, Julian was Milein’s most dedicated help and support. In the same way that he helped Hans carry on writing until the end of his life, so Milein also came increasingly to rely on his support for her artistic activities and they worked together for years on her exhibitions, publications and the mammoth task of sorting her archive.

After Hans’s death, Julian was Milein’s most dedicated help and support. In the same way that he helped Hans carry on writing until the end of his life, so Milein also came increasingly to rely on his support for her artistic activities and they worked together for years on her exhibitions, publications and the mammoth task of sorting her archive.

When Milein founded the Cosman Keller Art & Music Trust, Julian was naturally her choice for its chair. This webpage has been the story of all that has been achieved under his leadership.

When Milein founded the Cosman Keller Art & Music Trust, Julian was naturally her choice for its chair. This webpage has been the story of all that has been achieved under his leadership.

At the end of 2021, Milein’s centenary year, Julian decided to retire from the Trust, 15 years after its foundation, and 40 years after he began his regular visits to Frognal Gardens to help first Hans and then Milein.

Just before he stepped down, Julian received the welcome confirmation that Milein’s archive is to be acquired by Tate Archive in London. Tate Archive houses a wonderful collection of letters, diaries, drawings, sketchbooks, photographs and personal papers of artists who worked in Britain during the twentieth century, including a large collection from Milein’s great friend, Marie-Louise von Motesiczky.

With this major acquisition, and Julian’s retirement, this initial chapter of the story of Milein’s Trust comes to a close. As time goes on, the number of those who had the good fortune to know Hans and Milein personally will naturally diminish, but the legacy of these two remarkable people will live on, inspiring and supporting artists and musicians for many years to come.

![]()

© The Cosman Keller Art & Music Trust, 31 December 2021